The Diaghilev and the Ballets Russes: When Art Danced With Music exhibit, currently on display at The National Gallery of Art, captures the wonder of an influential team of artists that changed the course of fashion and the performing arts in the early part of the 20th Century.

Serge Diaghilev, Russian art patron and business man, created and ran the Parisian dance troupe from 1909-1929. Diaghilev aggressively courted some of the greatest European designers, painters, composers and dancers of the time. It is through collaboration with these exceptionally talented artists that the Ballets Russes would change the landscape of dance and influence a century of design.

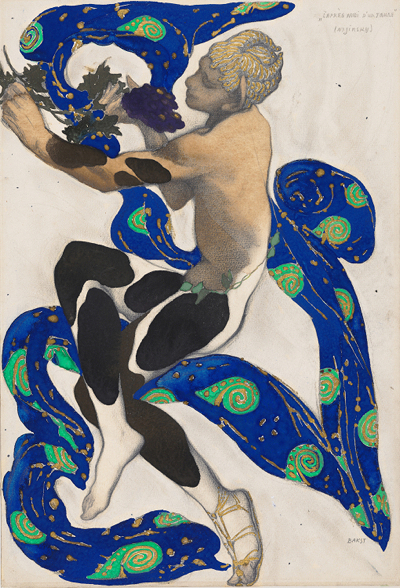

Leon Bakst costume rendering for The Afternoon Of A Faun (1912). [Credit: Diaghilev and the Ballets Russes, The National Gallery of Art]

The 19th Century ballet world was one of simplicity and romanticism, where classical choreography and traditional costuming had become the norm. Diaghilev challenged this perspective by introducing Parisian theatre-goers to highly athletic Russian dancers and wildly colorful sets and costumes that were heavily influenced by the Ancient East and abstract, cubist, and surrealist art.

The group of costume designers that Diaghilev recruited were all highly creative artists, already making a name for themselves as either painters or fashion designers, many of which have become household names even outside of theatre circles. Artists like Henri Matisse, Pablo Picasso, and fashion designer Coco Chanel are just a few influential designers whose costumes are featured in the exhibit.

Leon Bakst was one of Diaghilev’s early collaborators. His opulent set and costume designs utilized rich color, elaborate pattern, and a strong Eastern and folk influence. His bold designs for the production of Scheherazade (1911) featured a wonderful mix of sheers, patterns, and exotic silhouettes that proved an exciting and rather racy combination. Costumes that placed low, hip-hugging emphasis on female dancers and included bifurcated garments were quite a departure from the heavily corseted bodices and long tutus Parisian audiences had become accustomed to seeing.

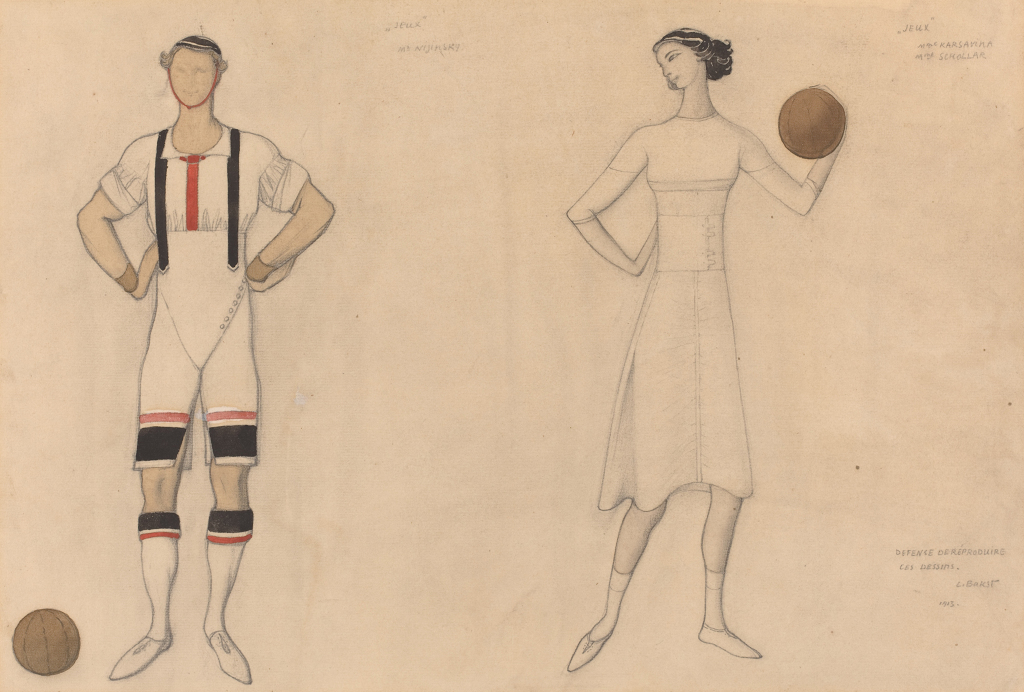

Costume Design by Leon Bakst, Scheherazade (1911). [Credit: Diaghilev and the Ballets Russes, The National Gallery of Art]

The costumes from The Afternoon Of A Faun (1912) are some of the most iconic by Bakst. The Faun’s costume rendering (which beautifully graces most of the promotional material for the exhibit, pictured above) shows off Bakst’s mastery of the human form and beautiful use of color. The costume itself is a simple unitard with patches of color, accompanied by an exquisite scarf. The costumes for the Nymphs for the same production are a stunning mix of hand painted sheer silk layered over pleated silver lamé.

Costume Design by Leon Bakst, The Afternoon Of A Faun (1911). [Credit: Diaghilev and the Ballets Russes, The National Gallery of Art]

Bakst’s costume design for The Blue God (1912) featured wonderfully elaborate patterns and ornate embroidery that created a kaleidoscope of color on stage. He beautifully combined Indian and Cambodian inspired clothing and headdresses.

Costume Design by Leon Bakst, The Blue God (1912). Credit: Diaghilev and the Ballets Russes, The National Gallery of Art]

Costume Design by Leon Bakst, The Blue God (1912). Credit: Diaghilev and the Ballets Russes, The National Gallery of Art]

Below you can begin to see the interrelationship of costume and fashion as they each seem to be inspiring one another both in shape and decoration.

Left: Costume Design by Leon Bakst, The Blue God (1912). [Credit: Diaghilev and the Ballets Russes, The National Gallery of Art] Right: Fancy Dress Costume by Paul Poiret, 1911. [Credit: Metropolitan Museum of Art] (Comparison by Jon Frederick, Fashion and The Ballets Russes: Costumes For A Modern World. NGA)

In the early years, Diaghilev also recruited Russian painter and art preservation activist Nicholas Roerich to design for The Ballets Russes. Roerich’s costume design for Prince Igor (1909) featured loosely fit garments for men made of gorgeously patterned Uzbekistan fabrics.

Costume Design by Nicholas Roerich, Prince Igor (1909). [Credit: Diaghilev and the Ballets Russes, The National Gallery of Art]

Roerich’s designs for The Rite of Spring (1913), featured flat, geometric shapes created through labor-intensive resist dyeing and hand-painting.

Costume Design by Nicholas Roerich, The Rite of Spring (1913). [Credit: Diaghilev and the Ballets Russes, The National Gallery of Art]

Diaghilev drew upon the incredible talents of progressive Russian painters Mikhail Larionov and Natalia Goncharova to design beautifully elaborate costumes. Through their productions they combined elements of cubism and traditional Russian folk art to create ground-breaking shapes for dance. Larionov’s costume design for The Tale of The Buffoon (1921) featured sculptural pieces achieved through the use of heavy felt, padding, and cane.

Costume Design by Mikhail Larionov, The Tale of The Buffoon (1921). [Credit: Diaghilev and the Ballets Russes, The National Gallery of Art]

Goncharova’s costume design for underwater tale Sadko (1916) are among the most beautiful pieces in the entire exhibit. Exquisite sea creatures are created through the use of hand-painted silks, wire shaped headpieces & tails, appliqués, and ombre fins.

Pablo Picasso, Spanish cubist artist, contributed to the legacy of the Ballets Russes with design for both set and costume design. His design for the Chinese Conjurer from Parade (1917) makes wonderful use of contrasting silk and hand stitched threads on clouds that create an incredible sense of depth, like cross hatch shading.

Costume Design by Pablo Picasso, Parade (1917). [Credit: Diaghilev and the Ballets Russes, The National Gallery of Art]

French painter Henri Mattisse’s use of shape and contrast to create beautifully minimalist patterns was put to good use when he designed the costumes for The Song of The Nightingale (1920).

Costume Design by Henri Mattisee, The Song of The Nightingale (1920). [Credit: Diaghilev and the Ballets Russes, The National Gallery of Art]

Many of the Ballets Russes’ costume designers also made significant contributions to fashion design of the early 20th Century. Sonia Delaunay, famed Orphism painter and textile artist, created the graphic and provocative designs for Cleopatra (1918). The iconic costume designed for the title character was not featured in the original exhibit at the Victoria & Albert Museum, but to the delight of visitors is on display at the National Gallery of Art, on loan from Los Angeles County Museum of Art. The costume features geometric quilting, heavy beading, and mirrored inlay.

Costume Design by Sonia Delaunay, Cleopatra (1918). [Credit: Diaghilev and the Ballets Russes, The National Gallery of Art. Los Angeles County Museum of Art]

Below you can see similar geometric detailing utilized by Delaunay in her fashion designs.

Fashion coats by Sonia Delaunay, 1920s.

One of the simplest, yet most exciting set of costumes to see in the exhibit are those designed for The Blue Train (1924) by Ballets Russes’ patron and famed couturier Coco Chanel. The costumes are a pair of knit bathing costumes that could easily be mistaken for 1920s sportswear. The simple cut of the man’s costume, complexity of colored knit of the woman’s costume, and the realization that you are gazing at items that Chanel herself would have fit on dancers is an incredible experience.

Costume Design by Coco Chanel, The Blue Train (1924). [Credit: Diaghilev and the Ballets Russes, The National Gallery of Art]

Chanel’s iconic minimalist aesthetic is just as evident in her costume design as it was in her fashion design.

Jersey sportswear, Chanel 1920s.

By far the most avant-garde costumes of the exhibit are those designed by Giorgio de Chirico and Pavel Tchelitchev. De Chirico, the Italian painter who wildly influenced the surrealist movement designed fantastically architectural costumes for The Ball (1929), featuring brick wall, column, and arch graphic motifs. The use of black outlining to create pieces such as the whimsical column cravat would have been just as stunning from stage as they are up-close.

Costume Design by Giorgio de Chirico, The Ball (1929). [Credit: Diaghilev and the Ballets Russes, The National Gallery of Art]

The Russian surrealist painter Tchelitchev’s breathtaking set and costume design for Ode (1928) beautifully depicted the movement of the constellations. Comprised of male dancers manipulating a system of wires, and female dancers dressed gorgeously as stars, these costumes are an early example of the use of artificial silk, ornamented with cellulous nitrate decorations, black hoods, and fencing masks.

Costume Design by Pavel Tchelitchev, Ode (1928). [Credit: Diaghilev and the Ballets Russes, The National Gallery of Art]

The work of the various designers of the Ballets Russes remain some of the most iconic costumes of the 20th Century and have served as inspiration for many costume and fashion designers since. The exhibit also consists of many set & costume renderings, as well as large theatrical backdrops. For the fashion, clothing, or theatre enthusiast, this exhibit is a must see, but those outside of these fields will find much to ogle and by which to be inspired!